Middle East middlemen: Canada, forever the peacekeeper, never the peacemaker

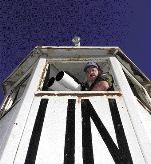

CAMP ZIOUANI, Golan Heights – From inside a creaky, rusty United Nations observation tower, a majestic view of the Holy Land unfolds. To the north, the snow-capped peaks of Mount Hermon. To the east, the plains of Syria. To the west, the hills of the Israeli-controlled Golan Heights glimmer in the sunset.

It’s early March and it is so quiet you can hear a UN flag flapping in the wind. It’s so serene you forget this is on one of the world’s most tense borders. “For the most part it stays peaceful and quiet,” said Capt. Barry Maddin of Ottawa, looking toward the horizon, “and I think we have a lot to do with that.”

Canadian soldiers have been here for more than 30 years, as part of UNDOF, the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force, a peacekeeping mission launched in 1974 after the Yom Kippur War between Israel and Syria. The Canadian contingent is helping to enforce the 75-kilometre long area of separation between the two countries. There are 190 Canadian soldiers in UNDOF, making it the second largest Canadian military commitment overseas, trailing only the operation in Afghanistan.

In peacekeeping, Canada found its niche. Peacekeeping became a pillar of Canadian foreign policy in the post-Second World War era, supposedly embodying the Canadian personality. It helps Canada advance the national image of an “honest broker” on the world stage. Peacekeeping missions have afforded Canada a vehicle to cultivate attributes of “impartiality” and “evenhandedness” and also differentiate itself from the United States. This has been particularly true in the Middle East, where Canada has sought to position itself between the U.S., which is currently perceived as pro-Israel, and Europe, which is currently regarded as pro-Arab.

Capt. Maddin, 51, a 34-year veteran of the military, is the maintenance officer of the force, now in its 83rd rotation. He and his soldiers are charged with the mechanical upkeep of the base and its equipment, including a large fleet of UN vehicles. “We grease the wheels.”

Not only literally, but figuratively. “I wouldn’t even want to guess what would happen if we pulled out tomorrow,” he said. “We provide a vital role. It’s pretty mundane — sometimes downright boring — but we keep the two warring parties separate.” Capt. Maddin filed his first request to be sent to the Golan Heights in 1975, as an eager 21-year-old soldier. He was denied. Thirty years later, he got his wish. More than 12,000 Canadian soldiers have served in the Golan during this time. Capt. Maddin finds himself maintaining a well-oiled machine that hasn’t changed much over this time and doesn’t look to change any time soon either.

– – –

A national mythology was born in 1957 when Lester B. Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the creation of the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF), deployed the previous year to help bring peace in Egypt, following the Suez Crisis. Throughout the Cold War, as superpowers watched from the sidelines, Canada responded positively to every United Nations request to participate in peacekeeping missions, solidifying its reputation as the leader in the field.

Middle East politics is a vicious sport, rife with reversals and betrayals, but Canada has floated above the fray. During the Suez Crisis, it was France and England who backed Israel while the U.S. pressured the Jewish state to withdraw. Today, the positions have all but reversed. Canada, though, has stayed firmly in he middle.

With no colonial baggage and little significant economic interests in the region, Canada has earned a unique role in this part of the world as an unbiased observer, one of the few countries to be accepted by all sides of the conflict. But is it really possible to have a significant role in the Middle East if you don’t declare where you stand on the Arab-Israeli conflict? Is “neutrality” a viable policy?

“Canada doesn’t have a policy in the Middle East,” says Martin Rudner, a professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University and director of the Canadian Centre of Intelligence and Security Studies. “We wish (Middle Easterners) well. We want peace, we want prosperity, we want good rains in winter, warm winds in summer, all the good things that people want, we wish. The problem is that’s not a foreign policy. Foreign policy is when you make hard choices, you determine what your objectives are and you make choices relative to your objectives. Wishing well is nice, but it is not a foreign policy.”

Mr. Rudner noted that Canada was not part of the Oslo negotiations, barely took part in the Madrid talks, and was not involved in the Egyptian-Israeli negotiations, the Jordanian-Israeli negotiations or the recent discourse over Syria’s military presence in Lebanon. “That’s where the real policy is made,” he said.

That’s also the distinction between “peacekeeping” and “peacemaking.” The first is a passive implementation of an existing status quo while the latter is an active effort of conflict resolution. Canada may be one of the world’s leading peacekeepers, but when it comes to peacemaking, we are non-existent.

– – –

Walking swiftly across camp from the officers’ mess to his office, Capt. Scott Usborne is all business. With a greying crew cut and sharp features, he gives the impression of a classic no-nonsense military man. A native of Victoria, he is, at 50, the senior captain on base.

He lays down the rules. No visitor is to leave the mess without an escort officer at all times. “This is an operational base,” he says. In mid-sentence, he draws his right hand to his brow and salutes in the direction of a small memorial in the centre of the camp. It’s a shrine dedicated to the 54 Canadian soldiers who have died in the Middle East, though only five belonged to UNDOF. (In all, 130 Canadians have died in peacekeeping missions around the world.)

The soldiers at Camp Ziouani salute the memorial each time they pass. It’s a reminder that danger is never far away. “People can still get killed here, even after 30 years,” he said.

Two months earlier, a French peacekeeper was killed by Israeli shelling in Lebanon, just north of here, while on patrol in the disputed Shebaa farms.

– – –

Canada first became involved in this part of the world in 1954 when it joined UNTSO, the observer force set up in 1949 to enforce armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria. UNTSO remains the longest standing UN mission and currently has eight Canadian observers in its force.

Then came UNDOF in 1974, and in 1986 Canada joined another, non-UN peacekeeping mission to monitor compliance by Israel and Egypt with the Camp David Peace Accords in the Sinai.

“Because of the unique geographical state of Canada, we have no external military threat,” said Capt. Usborne. “This gives us the luxury to use our army as a foreign policy tool.”

UNDOF is the largest and most substantial Canadian force in the Middle East. It continues to serve at the behest of both the Israelis and the Syrians, each of whom has asked Canada to reconsider its long-standing intention to scale back its forces in the region.

“Canada has no vested interest in what goes on between Israel and Syria other than being a good worldly neighbour — we want to see a long lasting peace here,” said Capt. Maddin. “When I talk to Israelis or Syrians, they don’t perceive Canada to be a pushy nation, or a nation sticking its nose in other people’s business.”

– – –

Lt.-Col. Shawn Myers has two emblems sewn onto the right sleeve of his uniform. One is the round blue symbol of the United Nations and the other is the red and white Maple Leaf of Canada. The two insignias symbolize the conflict with which every UN soldier is faced: the loyalty to one’s country and the loyalty to the multinational organization.

In Canada’s case, the conflict is muted because we have always been strong advocates of multilateralism, rarely surrendering our comfortable seat aboard the UN bandwagon.

Lt.-Col. Myers, the commanding officer of the Canadian contingent, called his Middle East experience “eye-opening” but would not disclose his personal impressions of the region and its politics, saying only that his force was a reflection of Canada’s commitment to the UN. He did, however, admit that “wearing the Maple Leaf gives you something extra.”

As a middle power with no historical prejudices, Canada can claim neutrality in a way that few countries can. With its bilingual officers (who have a linguistic entree into Europe), its membership in the British Commonwealth (which provides an entree into Africa and other places) and its proximity to the U.S., Canada can position itself as everyone’s friend and ally.

Michael Bell, a 36-year veteran of the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and a former ambassador to Egypt, Israel and Jordan, said the Canadian presence has a psychological impact in the region, serving as a reassurance to both sides that Canada and the world is still engaged in their conflict.

He rejected the terms “impartial” or “neutral,” preferring “fair-minded” instead. “It’s a desire not to avoid making judgments but a desire to avoid ganging up, avoid the appearance of being identified solely or largely with one party against the other.”

In Canada, strong pro-Israel and pro-Arab lobbies jockey for public and governmental support. It’s testimony to Canada’s skill in walking the tightrope that supporters of both Israel and the Palestinians agree Canada is — as Mr. Bell put it — fair-minded.

“(Canada’s) goal was always to find the third option, not the first option of the U.S. and not the second option of the Europeans,” said David Goldberg, director of Research and Education at the Canada-Israel Committee.

“Our government has consistently maintained a policy of balance,” echoed Hussein Amery, president of National Council on Canada-Arab Relations. “Canada doesn’t tilt one way or the other.”

In those rare moments when it does, the domestic players are quick to cry foul. In the late ’70s, then Conservative leader Joe Clark’s promise to move the Canadian Embassy to Jerusalem was quickly quashed after it was deemed too pro-Israel (because it would have bolstered Israel’s claim to all of Jerusalem.) In the late ’80s, Joe Clark was hammered from the other side for lifting the long-standing ban on meetings with the PLO. Then last year, Canada opposed two pro-Palestinian UN resolutions and the decision was examined under a microscope.

As a liberal western democracy, Canada has a natural connection to Israel, though it has stopped short of developing a “special relationship” with the Jewish state such as the Americans have. At the same time, Canada has pursued economic ties with many Arab nations. Like a happy bachelor, Canada can’t bring itself to choose between two girlfriends. Depending on the event, Canada is happy to be seen in public with either. “Canada tends to be pro-Israeli in politics and pro-Arab in trade,” said Mr. Amery.

– – –

Lt.-Col. Alain Lemieux, commander of the Canadian Middle East task force in UNTSO, was making a pit stop at Camp Ziouani en route to a meeting in Damascus. Based in Jerusalem, he oversees the seven other Canadian military observers spread across Egypt, Israel, Lebanon and Syria.

But he also serves another role as the military adviser to the UN special co-ordinator of the Middle East peace process. Given his status as both soldier and diplomat, he was more willing than others to delve into politics.

“People always come to Canada to listen to its voice,” he said, “and the reason, I believe, is because we can find those common threads and work them out.”

At the same time he admitted something else. “Canada is one step behind the big ones,” he said. “We are limited. Canada has its own limitations and everyone knows that.”

Despite all its good intentions and vaunted neutrality, Canada is not a heavyweight. “Both sides know that at the end of the day the Americans have the power and influence to assert themselves to a very important degree to make things stick, which we simply don’t have,” said Mr. Bell. He added, “Ours is a second-tier of involvement, but being a second-tier doesn’t mean it is not valuable.”

Soon, however, Canada may not even occupy a second-tier involvement, as the government is planning to scale back its UNDOF contingent from 190 troops to 40. The trend to reduce the presence of Canadian forces around the world has been ongoing for more than a decade. In 1993, there were 4,700 Canadian peacekeepers abroad. A dozen years later, that figure now stands at just over 1,500.

Yet others argue that Canada’s impotence has less to do with its military presence, or lack of it, than its political indecision. “We are

only received by both sides when all the problems are solved and you’re looking for the nice guys to come along and sing at the party,” said Mr. Rudner, the Carleton professor. “When there are hard decisions and hard negotiations we are not at the table because neither the Israelis nor the Palestinians or the Syrians know what Canada’s objectives are.”

The time has come, according to critics, for Canada to take a position. “If we had a policy which was in Canada’s national interest we would tell any one of these competing interests, which are all legitimate, we would tell them, ‘Sorry, Canada’s interests don’t coincide with your own,’ ” said Mr. Rudner. “The countries who are involved directly with the issues that are at stake, do not regard neutrality as a good thing. Neutrality is only a virtue for the neutral.”

Mr. Bell conceded that Canada might not have the domestic “stomach” to endure the criticism that would go along with a more involved role. “Sometimes you have to take risks and sometimes we are not willing enough to take those risks.” Or as Mr. Rudner put it, Canadians “dance between the raindrops, so we won’t get wet.”

While pro-Israel and pro-Arab activists in Canada would like the government to lean more in their direction, they agree that, either way, Canada can do much more. “Passive peacekeeping no longer has a function,” said Mr. Goldberg of the Canada-Israel Committee. “It’s an easy job, they don’t have to do anything. My sense is that Canada can do more than UNDOF.”

Mr. Amery said his Council on Canada-Arab Relations also wants the Canadian government to get more involved. “Canada needs to move from peacekeeping to peacemaking,” he said, almost exactly echoing Mr. Goldberg’s statements. The one thing Arab and Jew seem to agree on is that Canada needs to be more assertive.

– – –

The Middle East is bubbling. In Lebanon, former prime minister Rafik Hariri has been assassinated and the streets have overflowed with anti-Syrian demonstrators. Across the border in Syria itself, counter protests are underway. In Israel and the Palestinian Authority, people debate and protest over security fences, the Gaza withdrawal and the future of Jerusalem. But on the Golan Heights it all seems so far away. Here the Canadians enjoy their little slice of paradise.

The day at Camp Ziouani begins around 6 a.m. with physical exercise; some units jog, some hit the weight room, some play floor hockey. Then it’s a shower, a shave, a shoe shine and breakfast in the dining hall.

After that the troops dispatch to their various units, be it transportation, operations, supply maintenance, engineering or signals. If it weren’t for the landscape, and the fact that the base is surrounded by old minefields, the troops could be on any Canadian base in Petawawa or Cold Lake, Alta. The soldiers are patriotic and proud. They see themselves as ambassadors for their country.

No one more so than Capt. Brian Wentzell, the military chaplain, known on base as the Padre. “Being here in the Holy Land has got to be one of the most exciting and interesting experiences that we can get,” he said. “For me that’s a very biblical thing. We are serving one of the commands of Jesus, to serve the cause of peace.”

He reflects the general sentiment on base. “We see ourselves as being friends to either side,” he said. “We have no axe to grind.”

At night, the uniforms come off; it’s time to kick back and head for “the mess.” There is a clear delineation of power on camp: the soldiers congregate at “The Golan Club,” the warrant officers and sergeants fraternize at the “Eh-Line” and the 12 officers on base unwind in the small hut-like structure that is the officers mess.

Their lounge has a pool table, dart board, foosball table, stereo, television, DVD player and a bar.

Copies of the National Post and the Globe and Mail are on the table. The fridge is filled with cans of Labatt’s and Alexander Keith’s. A Bryan Adams song is playing. Thanks to Canadian Forces Radio and Television, you can hear The Bear 106.9 FM while you work out in the gym, or watch CJOH’s Max Keeping live over breakfast, delivering the previous day’s late night edition.

It’s a comfortable existence, befitting of a military base that hasn’t seen a bullet fired in its direction in more than 30 years. UNDOF’s five casualties did not die of hostile fire, but of illness, injury or accident.

– – –

In the officers’ mess one morning, Capt. Maddin takes off his beret and reflects on the past year. He is modest, mature and measured, which is also a good way to describe his team’s mission.

“I think the average Canadian soldiers don’t have the attitude to go out and kick ass,” said the Montreal native.

“We don’t have that kind of policy. We don’t have that kind of objective.”

It will soon be over for him. He’s been wearing a uniform since he was 13, when he joined the boy scouts. In just over three years he will retire and head home with his wife to her native Nova Scotia. “She’s been following me around for a while; now it’s time for me to follow her,” he said.

The family business will live on. Capt. Maddin’s father was a military man and both of his own children — a son, 25, and a daughter, 21 — are in the reserves. Conflict has been part of the Middle East landscape for generations. Thirty years down the road, the Maddin children could also wind up on some rocky outpost, playing referee just as their father did.

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT