AP PHOTOS: After Auschwitz, survivors still bear witness

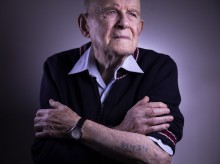

Mordechai Ciechanower, a 95-year-old Auschwitz survivor, shows his tattooed identification number as poses for a photo at his home in Ramat Gan, Israel. ( AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

Mordechai Ciechanower, a 95-year-old Auschwitz survivor, shows his tattooed identification number as poses for a photo at his home in Ramat Gan, Israel. ( AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

Seventy-five years after the killing stopped at Auschwitz, the survivors still bear witness, and many observe the rising hatred and anti-Semitism in the world today with a sense of deep disquiet.

Ahead of commemorations marking the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by the Soviet army, Associated Press reporters and photographers visited survivors in Germany, Poland, Sweden, Russia, the United States and Israel. Many posed showing the blue tattoos still imprinted on their arms, lifelong testaments of their suffering and loss — one of many ways they continue to warn new generations.

Today, the survivors are mostly in their 80s and 90s. The youngest was only two when the camp was liberated: Eva Umlauf is 77-years-old and still a practicing psychotherapist in Munich. She will be among hundreds traveling from countries around the globe where they settled after surviving the war to attend the ceremony at Auschwitz next Monday, exactly 75 years after the liberation, though some are too frail to go.

Auschwitz was the most notorious in a system of concentration and extermination camps that Nazi Germany built across Europe. It was operated in occupied Poland, home to Europe’s largest Jewish population, and at the heart of a railway network that allowed the Nazis to easily transport Jews there from elsewhere across the continent.

The old and infirm were quickly shuttled to their death, often through the iconic watchtower entrance to Birkenau, while those still deemed well enough to serve the Nazi war machine were shepherded through the pathway where the cynical “Arbeit Macht Frei” sign was placed, promising that “work sets you free.”

It didn’t. They were tattooed, hosed down, sheared of their hair and put to slave labor. Provided little clothing or food, they were rammed into cramped barracks locked in behind barbed wire fences. Most withered away before ending up in the crematoria or marched off to their deaths elsewhere as the allies closed in and liberated the camp on Jan. 27, 1945, a date the United Nations has since acknowledged as International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In all, the Nazi German forces killed 1.1 million people at Auschwitz, most of them Jews, in a meticulous German effort to rid Europe of its Jews in a plan dubbed the “Final Solution.”

Overall, the Holocaust claimed 6 million Jewish lives, wiping out a third of world Jewry.

Mordechai Ciechanower, a 95-year-old Auschwitz survivor living in Ramat Gan, Israel , says he survived his nearly two years in the camp thanks to his roofing skills and the generous help of others.

“I died hundreds of times, but kept getting up,” he said. “I never thought I would get out of there, let alone live this long.”

The widowed Ciechanower now has six grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren, and the walls of his apartment are packed with plaques acknowledging his service for leading delegations to visit former concentration camps.

He is not alone in devoting himself to Holocaust education. Many survivors still speak to young people and volunteer in Holocaust museums.

Marta Wise, an 85-year-old Auschwitz survivor, was a sickly 10-year-old girl who was among just several thousand inmates who remained at Auschwitz on the day it was liberated after most had been marched off to die elsewhere. She now volunteers as a guide at the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial and spends time with her 14 grandchildren and many great-grandchildren.

Leon Weintraub, a 94-year-old Polish Jew who lives in Stockholm, is horrified by the rising far-right extremism in his homeland, where even some small fringe neo-Nazi groups exist. “This is unbelievable that descendants of Poles killed by the Nazis call (themselves) today Nazis,” he said.

Survivors are also deeply troubled to see politicians seeking to win political points with memories of the war.

A 96-year-old Polish Catholic survivor of Auschwitz and the Ravensbrueck camp, Zofia Pomysz, began to shake with rage when asked about Russian President Vladimir Putin seeking now to shift blame for the war onto Poland, which was the war’s first victim. “It’s despicable,” she said, recalling how she and her family were fleeing the invading Germans in 1939 only to be told that Soviets had invaded from the east.

Yevgeny Kovalev, a 92-year-old Russian who was imprisoned in Auschwitz from 1943-44 for helping Soviet partisans blow up railways and trains to sabotage the Nazi invaders, recalled whippings so brutal that his shirt became drenched in blood.

“Remembering all that is always like torture for me, can you imagine that. I’m even wondering myself how I could survive those time,” Kovalev said.

At age 98, Leon Schwarzbaum, a retired art dealer, still lives on his own in his Berlin apartment, the walls covered with paintings and old back-and-white pictures of his 35 relatives who perished in the Holocaust. He said he is too frail to travel to Auschwitz, but still goes to schools in Germany regularly to tell the children about the unbearable sufferings he lived through at the death camp.

Schwarzbaum said he is deeply worried about the expanding anti-Semitism in Europe.

“If things get worse, I would not want to live through such times again,” he said. “I would immigrate to Israel right away.”

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT