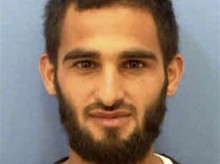

Bedouin Israeli doctor mysteriously turns jihadi

HURA, Israel (AP) — He was a quiet whiz kid at the top of his class in Israel, who overcame tough odds in this minority Arab village to become a star medical student and hospital intern.

Could Othman Abu al-Qiyan have been radicalized by Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians — or something else?

No one can quite explain what happened and why, but in his community in Israel’s southern Negev desert, where many even serve in the Israeli army, his sudden transformation into a jihadi killed in Syria fighting for the Islamic State group is treated as a dark and dangerous mystery.

In three years of war in Syria, dozens of educated and seemingly progressive Muslims from Western countries have been lured to what they perceive to be a heroic jihadi battle against President Bashar Assad.

In Israel, the phenomenon is still marginal. Israel’s Shin Bet security service estimates that only about 30 Arabs have departed for Syria to take part in the fighting. Just a handful have joined IS — the extremist group notorious for its beheadings of foreign journalists and aid workers.

Abu al-Qiyan, believed to be in his late 20s, is the first Bedouin to take that route. His extended family — which has close ties to the Israeli establishment and has produced many soldiers — has been quick to condemn and distance itself from the act.

“I know the father, I know the grandfather, they are good people,” said Salim Abu al-Qiyan, a distant relative who said the family has posthumously disowned the deceased jihadi for shaming them.

“They have no idea why he went there and how he did it. They invested a lot of money in him, they taught him and made a doctor out of him and they were waiting to reap the benefits. And this person showed no signs, he did not tell anybody, he went on a normal trip.”

The Bedouin are among the most underprivileged communities in Israel, and have become more religious in recent years. They have been particularly enraged at the Israeli establishment over plans to resettle their traditionally nomadic communities into government-recognized villages.

Even so, IS seems a world away, especially for someone like Abu al-Qiyan. He was a golden boy, described by those who knew him as a shy “genius” who was equally devoted to medicine and Islam.

“He was very smart, very sharp. The last person you would have suspected to be violent,” said Dr. Yosef Mishal, a department head at Barzilai Medical Center who oversaw Abu al-Qiyan’s internship. “He is the kind of doctor any department head would want.”

Abu al-Qiyan was set to start a further specialization at Beersheba’s Soroka hospital in May when he vanished.

What followed next remains unclear: Residents in Hura were hesitant to discuss details openly either because of the shame it brought upon them or for fear of angering his extended family, one of the two most powerful clans in town.

Several family members said all they knew is that he left for what he said was a vacation in Turkey with a cousin. They said Abu al-Qiyan later called them from Syria, telling them where he left his belongings and saying he would meet them next in paradise.

Some traveled to Turkey in a desperate attempt to find him and bring him back. Family members said they got an anonymous call in August saying that he had been killed in the first wave of American air raids against the Islamic State.

His exact role within IS, as a medic or perhaps a fighter, is unknown. The relatives spoke on condition of anonymity because they did not want to cause trouble in the family.

Locals have speculated that Abu Al-Qiyan was radicalized while studying in Jordan or that he was secretly recruited online. But no one has attested to hearing him say anything that indicated that. Even the Shin Bet, which closely monitors suspected extremists, is at a loss to explain a motivation. It has arrested Abu Al-Qiyan’s brother, Idris, on suspicion of aiding him but said it has no further intelligence on the doctor or his relative Shafiq, who accompanied him to Turkey and whose fate remains unknown.

Bedouins make up a small group within Israel’s Arab minority, numbering about 180,000. Some live in organized townships like Hura, home to about 14,000 people, while others still reside in desert tents to stay closer to their nomadic traditions. Historically, the Bedouin in Israel have identified more closely with the Jewish state than other Arabs, and many serve in the military, where they have their own combat battalion and are highly respected as desert trackers.

While some have expressed general support for the greater goal of an Islamic caliphate espoused by IS, there have been no signs of overt backing for the jihadis, said Suleiman Azbarga, a 29-year-old local businessman who studied with Abu Al-Qiyan in Jordan.

He said he was shocked by the news about his old acquaintance, who he remembered as being extremely bright.

“It is impossible to describe the feeling,” he said, out of sight of suspicious eyes in town. “There may be a few who feel pride in this, but these are very, very few. The majority of people here feel disappointment, and a sense of loss.”

Yousef Abu Jaffer, the Western-educated treasurer of the Hura municipality, said there was “something there” that was attracting seemingly successful youngsters to trade in a life of promise for a suicidal quest in the name of religion.

“He (Abu Al-Qiyan) is the right profile for success,” he said. “No one will answer the clear question: what happened there? But somebody has to do that.”

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT