Ex-Israeli security chiefs largely favor peace

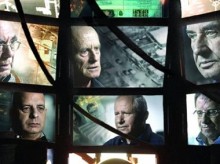

JERUSALEM (AP) — Israel’s Academy Award-nominated documentary “The Gatekeepers” has won rave reviews for the candid soul-searching of its chief protagonists — the six living former directors of the country’s shadowy domestic spy agency — and their somewhat surprising conclusion: That force has its limits and Israel must ultimately take advantage of its military superiority to seek peace.

It’s no surprise, though, in Israel. Top security officials have a long history of favoring dovish political parties and criticizing government policies toward the Palestinians after their retirements. Those who have battled Palestinian violence with the harshest methods possible are oddly those often most amicable to compromise.

“These moments end up etched deep inside you, and when you retire, you become a bit of a leftist,” Yaakov Peri, who led the Shin Bet agency from 1988 to 1994, says in the film.

In a phone interview with The Associated Press, Peri cited the well-known axiom that those who have actually used force know best its limitations and its heavy price.

“The moment you are there, at the heart of the conflict and the fight against terror, you begin to think deeply about how to end the conflict,” said Peri, who was recently elected a lawmaker from the centrist Yesh Atid Party. “Just force, just battle, just deception won’t bring peace between the nations.”

He and his fellow Shin Bet directors are not typical bleeding hearts. The post is so secretive that until recently, the director was only known to the public by his first initial, and his identity disclosed only upon retirement.

None have qualms about the essential task of the organization they headed or the tactics they have employed, which some have called brutal. It’s not about being dovish, Peri said, it’s about being realistic.

“We present a facet of liberal, democratic, independent thinking,” he said. “The film lifts some of the mystery over a group that is typically regarded as harsh, dangerous and mysterious. And I think that is a good thing.”

The trend goes far beyond the Shin Bet.

The late Yitzhak Rabin, one of Israel’s greatest generals, reached a landmark interim peace agreement with the Palestinians before he was assassinated by a Jewish ultranationalist in 1995. As prime minister, Ehud Barak, another former military chief of staff, led an aggressive push for peace before the talks disintegrated in a burst of violence in late 2000.

Two other former chiefs of staff, the late Amnon Lipkin-Shahak and Shaul Mofaz, also took dovish positions after entering politics. Meir Dagan, the recently retired chief of the Mossad spy agency, has been openly critical of the Israeli leadership’s alleged plans to attack Iran’s nuclear program and former military chief Gabi Ashkenazi also reportedly clashed with his superiors over policy.

Yuval Diskin, who recently retired as Shin Bet chief and is one of the subjects profiled in “The Gatekeepers,” told an Israeli newspaper on the eve of elections last month that Israel deserved “better leadership” and said Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had missed opportunities to advance peace. He said he had based his opinion on dozens of discussion with people of his rank.

Shaul Arieli, a member of the Council for Peace and Security, a dovish grouping of retired high-ranking officers, estimated that about 90 percent of ex-senior security officials tend to take moderate positions on war and peace.

“Our experience tells us that national security is more than what you see between the crosshairs (of a rifle),” said Arieli, a retired colonel. “We believe that peace will provide better security than anything else.”

He said the trend was unique to Israel, where military service was mandatory and the conflict closer to home.

The lone exception in recent years has been Moshe Yaalon, another former military chief who is the currently a hard-line vice premier from the ruling Likud Party. Yaalon refused an interview request.

“The Gatekeepers” nomination is a rare nod in the Best Documentary Feature category, which is typically dominated by American productions. This year a second film about Israel’s separation barrier with the West Bank, “Five Broken Cameras,” is also up for consideration in the category.

In an added ironic twist, the films, both highly critical of Israeli policies, received funding from the Israeli government. Like many countries around the world, particularly in Europe, Israel has a national film fund that helps subsidize local productions, with little oversight of their content.

“The Gatekeepers” already has won several awards, including The National Society of Film Critics’ best nonfiction film award and the Los Angeles Film Critics Associations’ best documentary prize.

Among the highlights of the film are comments by Ami Ayalon, an ex-naval general who ran the Shin Bet from 1996 to 2000. “We’re winning all the battles … and we’re losing the war,” Ayalon said.

Inside Israel, the film has not created as much of a buzz. Perhaps that’s because the Palestinian issue has been pushed to the backburner after four years of deadlock, or because people have grown numb to the conflict and no longer think peace is possible. But several Israeli columnists have said it should be required viewing for Israelis.

“For lovers of Israel, the Oscar-nominated film is like a waterboarding of the soul,” Chemi Shalev wrote in the liberal Haaretz daily.

His colleague, Bradley Burstein, urged President Barack Obama to watch the film before he visits Israel next month. “Mr. President, if you haven’t already, watch ‘The Gatekeepers’ on the biggest screen you’ve got,” he wrote. “You need this writ large because these men explain Israel.”

It’s unclear if Obama has seen the film, but one leader who definitely has not is Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. His office said it wasn’t a matter of policy, but rather than the premier had more pressing matters to address.

Several retired security chiefs have expressed frustration toward Netanyahu, saying they waged years of war to provide security and calm environment for the political level to engage in a peace process and it hasn’t happened. Netanyahu blames the Palestinians for the deadlock.

“We managed to lower the terror threat to a level that enabled Israelis to live a normal life for an extended period,” said Danny Yatom, a former military general and Mossad chief. “They didn’t take advantage of this period and did nothing with the calm.”

After 35 years of service, Yatom joined the dovish Labor Party and became of staunch supporter of a two-state solution with the Palestinians.

“Part of the dovish outlook comes from the realization that a conflict between people cannot be solved by military means alone. It has to be integrated with diplomacy,” he told the AP. “We have to be strong and fight terror with all our might but military actions can only suppress terror. … You can’t defeat it entirely without a diplomatic option.”

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT