Israeli cousins united by Holocaust database

JERUSALEM (AP) —Ever since she became an orphaned 12-year-old in Russia, Liora Tamir thought she was alone in the world—having lost every single member of her family either in the Nazi Holocaust or Soviet prison camps.

That changed because of a recent search of a database of names of Holocaust victims. She discovered that her murdered grandparents were commemorated there by an uncle she never knew, who had moved to Israel.

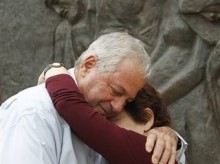

On Thursday, she was united with his son—her cousin—at an emotional ceremony at Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem.

“My mother didn’t tell me anything about the family, I thought they were all gone,” said Tamir, 65, shortly after embracing 73-year-old Aryeh Shikler. “Now I have a cousin. I still can’t believe it. It’s surreal.”

Tamir’s daughter, Ilana, made the reunion possible. For years she scoured archives for any information about her maternal grandmother, Yona Shapira.

Initially, she learned that her grandmother traveled from Poland to pre-state Israel in the 1920s and spent six years there before she was arrested and deported by the British because of her communist activities. These activities ultimately landed her in the Gulag town of Vorkuta where Liora was born.

Then, KGB documents she obtained revealed the names of Shapira’s parents. Finally, she searched Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims Names and found a page of testimony under their names submitted in 1956 by a Simcha Shikler—Aryeh’s father. Shoah is the Hebrew term for Holocaust.

“It definitely feels like I cracked a mystery and we now we have a better picture of our family,” said Ilana Tamir, 33. “I feel like I gave my mother a gift, I gave her a family. We had a hole in our hearts, and we didn’t have a family or blood relationships with anyone—and suddenly a family was born.”

Cynthia Wroclawski, the manager of Yad Vashem’s name recovery project, called the database “the repository for the Jewish people” that allowed people like Tamir to peel away crucial information about their own family histories.

“I think everyone at some point in their life becomes interested in where they came from to see where they’re going and the story of Liora Tamir is one such story,” she said.

Yad Vashem’s goal is to collect all 6 million names of the Holocaust’s Jewish victims, encouraging survivors to come forth and fill out pages of testimony for those killed, before their names and stories are lost forever.

The project began in 1955 and had reached 3 million confirmed names by the time the online database was launched in 2004. More than a million more names have been added since. The information can be accessed online in English, Hebrew and Russian.

Efforts continue, primarily in eastern Europe, where name collection is particularly difficult because Jews there were often rounded up, shot and dumped in mass graves without any documentation. The names of Jews killed at German death camps, on the other hand, often remain because of meticulous Nazi records.

Hugging his cousin for the first time, the gray-haired Shikler said the joy of the moment was mixed with sadness over those who couldn’t witness it. He, too, knew little about his family history.

Of their grandparents’ five children, two perished in the Holocaust, Shikler’s father came to Israel, Tamir’s mother died in Russia and another sibling emigrated to the United States, never to be heard of again.

The two cousins live an hour away from each other—Tamir in Tel Aviv, Shikler in Haifa. They say they have much to share and much to learn.

“We are connected by blood,” Shikler said, in a scratchy voice. “All you need to do is listen and it all starts flowing out.”

Tamir’s daughter said the situation would take some getting used to.

“All of a sudden we have a family tree. Until now it was just one branch,” she said. “I don’t know what you do with family because it is really strange and new for us.”

———

Online: http://www.yadvashem.org/

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT