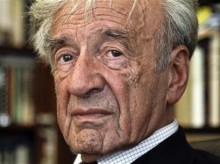

Israelis mourn Elie Wiesel as one of their own

JERUSALEM (AP) — Elie Wiesel never lived in Israel, but on Sunday the country mourned the death of the esteemed author and Nobel peace laureate as though it had lost a national icon.

A frequent visitor who was fluent in Hebrew, Wiesel was a confidant of prime ministers and a towering cultural figure so revered that two premiers considered nominating him to be the country’s ceremonial president.

His unwavering support for Israel proved divisive at times, with critics arguing that he ignored the suffering of the Palestinians and backed Israeli settlements. He also waded into last year’s debate over the nuclear deal with Iran, attending an address by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to the U.S. Congress that angered the White House.

As perhaps the world’s most famous Holocaust survivor, Wiesel was championed by Israeli leaders as a symbol of the Jewish people’s journey from the depths of despair to the redemption of having a land of their own. His enduring legacy of “Never Again” mirrored the psyche of a nation built on the ashes of the Nazi genocide of 6 million Jews and facing constant strife in the Middle East.

“Your voice will continue to be heard. It is ingrained in our nation,” eulogized Shimon Peres, the former president and a fellow Nobel peace laureate. “Our people have known darkness and terrible danger, but also amazing rebirth. This is what allows us to continue on.”

Wiesel’s connection to Israel began immediately after it gained independence in 1948, when he arrived to the newborn state as a foreign correspondent for a French newspaper. He later worked as a roving reporter for an Israeli daily.

He moved to New York in 1956, and gained fame with the publication of his landmark Holocaust book “Night.” He became an American citizen, published dozens of books and later hobnobbed with presidents who welcomed him to the White House and tasked him with planning an American Holocaust memorial museum. He received the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

But in many ways his heart remained in Israel, a place he visited three times a year. In 1961, he covered the trial of Nazi mastermind Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. In 1969, he married his wife there.

In his words of commemoration, Netanyahu said Jerusalem “represented to him our ability to rise from the pit and reach new heights.”

“The memory of this man, who taught us what memory is, will be enshrined in our hearts and in the heart of humanity forever,” he said.

Wiesel was a driving force behind the establishment of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. His words, “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness,” are engraved in stone at the entrance to the museum. He was also a vice chairman of the council of Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial and worked closely with many of its researchers.

He established a synagogue in Jerusalem in honor of his father, who perished in the Holocaust, and a pair of institutions in southern Israel named for his slain sister that were devoted to after-school programs for Ethiopian immigrants, said Dina Porat, the chief historian at Yad Vashem and a friend of 30 years.

“He wasn’t a citizen of Israel, but he was a true lover of Israel,” she said. “He was an ambassador for the country even though no one appointed him.”

Porat said Wiesel made a personal decision to never openly criticize Israel, and stuck to his word even as he came under fire from fellow humanitarians.

Wiesel said little about the plight of Palestinians living under Israeli occupation, and his association with Elad, a hard-line organization that settles Jewish nationalists in the heart of Arab neighborhoods in Jerusalem, angered critics.

“Wiesel supported human rights for everyone but for Palestinians, where he advocated for most Israeli policies against our people,” Xavier Abu Eid, a Palestinian official, wrote on his Twitter feed.

Wiesel’s advocacy for Israel went far beyond Holocaust commemoration. Despite his close relationship with President Barack Obama, he took out advertisements in four major newspapers in 2010 that criticized the Obama administration for pressuring the Netanyahu government to halt settlement construction in Jewish areas of east Jerusalem, the part of the city captured in 1967 and claimed by the Palestinians.

“When a Jew visits Jerusalem for the first time, it is not the first time,” Wiesel wrote in the ad. “It is a homecoming.”

In 2013, he took out a full-page ad in The New York Times calling on the U.S. administration to demand the dismantling of Iran’s nuclear facilities because it had called for Israel’s destruction. Last year, he was a guest of Netanyahu when the Israeli leader delivered a controversial speech to the U.S. Congress railing against the nuclear deal with Iran. Wiesel sat in the audience, waving to the crowd as the Israeli leader alluded to the Nazis while describing the Iranian threat.

Wiesel’s connection to Israel was so close that in 2007, then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert reportedly suggested nominating Wiesel as a candidate for president, even though he wasn’t a citizen. Netanyahu later considered doing the same.

Although Wiesel spoke Hebrew, in many ways, he was a bigger figure abroad than in Israel, perhaps because the country has so many other well-known Holocaust authors and historians as well as a large but dwindling community of survivors.

His passing is a harbinger of a looming post-survivor era, as the number of survivors continues to decline, and those who remain are either too old to recollect clearly or were children at the time of the Holocaust.

Yehuda Bauer, one of Israel’s foremost Holocaust historians and a longtime acquaintance of Wiesel’s, said Wiesel always “wanted to be involved” with Israel but never wanted to live in the country.

“He wanted to sort of support it from the outside,” Bauer said. “He was a man of the world. He didn’t want to limit himself to a small country.”

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT